Table of Contents

What is Schistosoma haematobium?

- Schistosoma haematobium (urinary blood fluke) is a species of the digenetic trematode Schistosoma, which belongs to the blood fluke genus Schistosoma (Schistosoma).

- Africa and the Middle East are its natural habitats. Schistosomiasis, the most widespread parasite infection in humans, is caused by this organism.

- It is the major cause of bladder cancer and the only blood fluke that infects the urinary tract, causing urinary schistosomiasis (only next to tobacco smoking). The eggs are the cause of the disorders.

- Adults are located in the venous plexuses surrounding the urinary bladder, and the released eggs move to the bladder wall, causing haematuria and fibrosis.

- With hydronephrosis, the bladder becomes calcified and there is increased pressure on the ureters and kidneys. S. haematobium-caused inflammation of the genitals may lead to the spread of HIV.

- S. haematobium was discovered as the first blood fluke. In 1851, Theodor Bilharz, a German surgeon working in Egypt, recognised the parasite as the culprit responsible for urinary tract infections.

- The infection (usually comprising all schistosome infections) was named bilharzia or bilharziosis after its discoverer. In 2009, the WHO International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Working Group on the Assessment of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans classified S. haematobium as a Category 1 (extensively proved) carcinogen, among fellow helminth parasites Clonorchis sinensis and Opisthorchis viverrini.

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Platyhelminthes |

| Class: | Trematoda |

| Order: | Diplostomida |

| Family: | Schistosomatidae |

| Genus: | Schistosoma |

| Species: | S. haematobium |

Characteristics of Schistosoma haematobium

- Size and shape: Mature Schistosoma haematobium worms are between 6 and 20 mm in length and have a flattened, elongated form.

- Lifecycle: The complex lifecycle of Schistosoma haematobium involves an intermediate host (a freshwater snail) and a definitive host (humans). Adult worms reside in the veins that drain the bladder, where they lay eggs that are expelled by urine.

- Transmission: Schistosoma haematobium is transmitted to humans when they come into touch with contaminated waters that contains the intermediate host snail. The snail’s larvae enter the epidermis of the human host and move to the bladder veins, where they mature into adult worms.

- Symptoms: Symptoms associated with Schistosoma haematobium infection include bloody urine, stomach pain, and diarrhoea. Chronic infections can cause damage to the bladder and kidneys.

- Treatment: Praziquantel, an antiparasitic medicine that kills adult worms, is the most common treatment for Schistosoma haematobium infection. Access to clean water and good sanitation are also effective in preventing the spread of the disease.

Structure of Schistosoma haematobium

- Male and female adults of Schistosoma haematobium are permanently paired (a condition known as copula) as what seems to be an individual. The male flatworm measures between 10 and 18 mm in length and 1 mm in width.

- It possesses oral and ventral suckers at the anterior end. The female is encased in a channel or groove known as the gynaecophoric canal, which is formed by the flattening of the leaf-like body on both sides.

- Hence, it has the general look of a worm with a cylindrical body. Just the anterior and posterior extremities of the female are visible. In contrast to the male, the female possesses all characteristics of a roundworm.

- About 20 mm in length and 0.25 mm in width, it is cylindrical and elongated. Its infectious weapon, the eggs are oval, 144 × 58 µm in diameter, and have a distinctive terminal spine. Co-infection with S. mansoni (which has lateral-spined eggs) is prevalent, hence this is a useful diagnostic tool.

- The miracidium is approximately 136 m in length and 55 m in width. The body is coated with epidermal plates that are anucleate and divided by epidermal ridges.

- Epidermal cells emit many hair-like cilia on the surface of the body. Only in the apical papilla or terebratorium, which contains several sensory organelles, is the epidermal plate absent. Its body is almost entirely composed of glycogen granules and vesicles.

- The unique bifurcated tail of the cercaria is called furcae (Latin fork); hence the name (derived from the Greek word o, kerkos, which means tail). The body’s length and width are 0.24 mm and 0.1 mm, respectively. Its skin is completely covered with spines. A prominent oral sucker is located at the apex of the body.

Geographic Distribution

- The parasitic flatworm Schistosoma haematobium produces the disease known as urogenital schistosomiasis. It is found predominantly in sub-Saharan Africa, but also in portions of the Middle East and southern Yemen.

- Schistosoma haematobium’s distribution is tightly linked to the occurrence of freshwater snails, which serve as intermediate hosts for the parasite. The snails discharge cercariae into the water, which are the infective stage of the parasite. When individuals come into contact with contaminated water, the cercariae can infect them through their skin.

- Schistosoma haematobium is most prevalent in regions with inadequate sanitation and limited access to clean water, where people are more likely to consume polluted water. Moreover, it is more widespread in rural regions than in metropolitan ones.

- Generally, Schistosoma haematobium is restricted to places where intermediate snail hosts are available and human populations are at danger of exposure to contaminated water sources.

Habitat

- The parasitic flatworm Schistosoma haematobium has a unique home within the human body. Schistosomiasis is caused by the parasite’s primary presence in the veins surrounding the urine bladder and the reproductive organs.

- However, Schistosoma haematobium’s life cycle involves multiple phases outside of the human host, and the parasite requires particular environmental conditions to survive. The adult worms create eggs that are expelled from the human body in urine or faeces, contaminating freshwater sources.

- Once the eggs hatch in freshwater, the parasite’s first-stage larvae, miracidia, are released. Infected freshwater snails serve as intermediary hosts for the miracidia. Miracidia evolve into cercariae, the free-swimming, infectious stage of the parasite, within the snails.

- Schistosoma haematobium’s habitat consists of freshwater snails and freshwater sources contaminated with the parasite’s eggs. The snails and polluted water offer the required conditions for the parasite’s life cycle to continue, hence perpetuating the disease’s transmission.

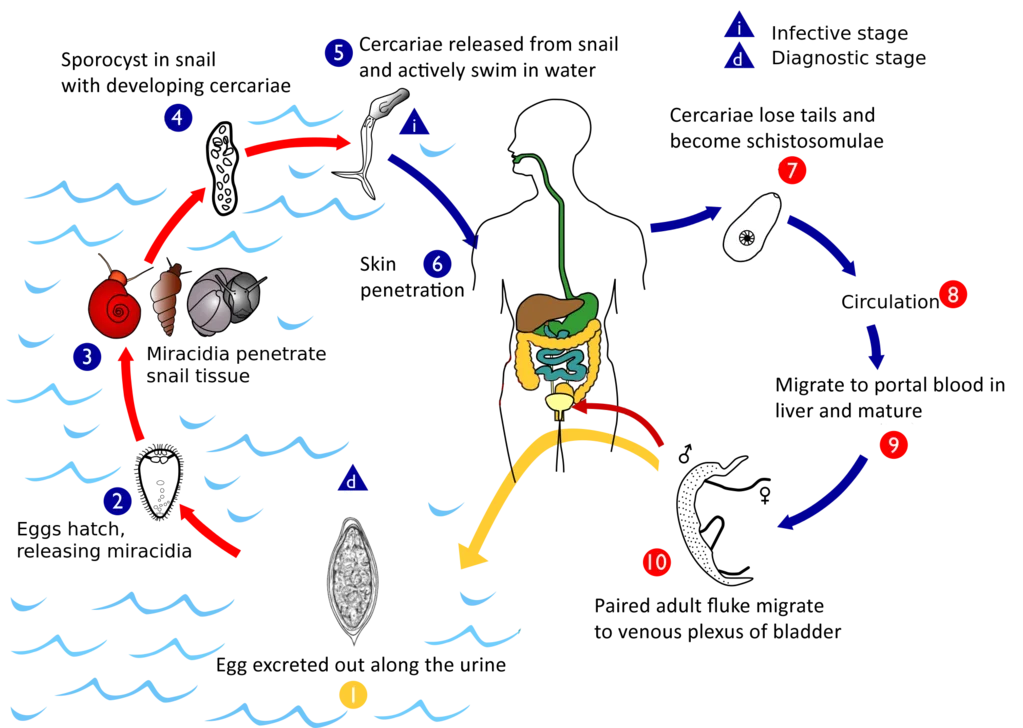

Life cycle of Schistosoma haematobium

- Like with other schistosomes, S. haematobium completes its life cycle in humans as definitive hosts and in freshwater snails as intermediate hosts.

- In contrast to other schistosomes, which release their eggs in the intestine, this parasite releases its eggs in the urinary tract, which are then excreted with the urine. In stagnant freshwater, eggs hatch into larvae known as miracidia after 15 minutes.

- Every miracidium is either masculine or feminine. Miracidia are covered with hair-like cilia that actively look for snails while swimming. Unless they infect a snail within 24–28 hours, they exhaust their energy reserves (glycogen) and perish.

- Miracidia can be carried by snails belonging to the genus Bulinus, including B. globosus, B. forskalii, B. nasutus, B. nyassanus, and B. truncatus. The miracidia simply penetrate the snail’s delicate skin and travel to the liver.

- Within twenty-four hours, the snail’s cilia are shed and an extraepithelial coating forms. After two weeks, they change into sporocysts and engage in active cell division. Many offspring sporocysts are produced by the mother sporocyst. Each daughter sporocyst produces new cercariae larvae.

- One sporocyst mother generates 500,000 cercariae. After a month, the sporocysts rupture, releasing cercariae. Free cercariae pierce the liver and exit the snail into the surrounding water.

- Each cercaria has a two-pronged tail that it uses to swim in search of a human host. The cercariae are short-lived and can only survive in water for 4–6 days if they do not locate a human host.

- Possible involvement of the Planorbarius metidjensis snail, which is native to Northwest Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, however experimental infections are the sole source of conclusive data.

- When a human comes into touch with water containing cercariae, the cercariae attach to the skin via their suckers. After correct orientation, they begin to pierce the skin by secreting proteolytic enzymes that enlarge skin pores (hair follicles).

- This procedure takes around 3–5 minutes and is accompanied by itching, but by this time the insects have already pierced the skin. Their tails are cut off upon entry, allowing just their heads to enter. As these parasites reach the blood vessels, they are referred to as schistotomulae.

- They enter the circulatory system to reach the heart and eventually the liver, and many are eliminated by immune cells along the way. Surviving individuals enter the liver within 24 hours. From the liver, they enter the portal vein to reach other bodily areas.

- The schistosomulae of S. haematobium, unlike those of other species, reach the vesical vessels via anastomotic channels between the radicles of the inferior mesenteric vein and the pelvic veins. After residing in small venules in the submucosa and wall of the bladder, they migrate to the perivesical venous plexus (a collection of veins in the lower section of the bladder) to mature.

- In order to avoid detection by the host’s immune system, adults might cover themselves with host antigen.

- Persons separate out opposing sexes. The female body becomes encased within the male’s rolled-up gynaecophoric canal; hence, they become lifelong companions. Sexual maturity is achieved four to six weeks after initial infection. On average, a female lays 500–1,000 eggs every day.

- The female leaves the male only momentarily to lay eggs. Only it can access the small, narrow peripheral venule in the submucosa in order for the eggs to be discharged into the bladder. The embryonated eggs pierce the bladder mucosa with the aid of proteolytic enzymes, their terminal spines, and bladder contraction.

- The enzyme is a toxin that selectively causes tissue death (necrosis). Under normal circumstances, the discharge of eggs into the bladder does not result in pathological symptoms. Nevertheless, eggs frequently fail to pierce the bladder mucosa and become caught in the bladder wall; it is these eggs that cause lesions by releasing their antigens and causing the formation of granulomas.

- Granulomas consolidate to create tubercles, nodules, or masses, which are frequently ulcerated. This disorder is the cause of pathological lesions in the bladder wall, ureter, and kidney, as well as benign and malignant tumours. The fluke lays eggs continually throughout its lifetime. The usual lifespan is three to four years.

Pathogenicity of Schistosoma haematobium

- Normal adult infection does not generate symptoms. Sometimes, when eggs are discharged, they become permanently lodged in the bladder, causing pathological symptoms.

- The eggs are initially deposited in the muscularis propria, resulting in ulceration of the tissue above. Infections are distinguished by prominent acute inflammation, squamous metaplasia, blood, and reactive epithelial alterations.

- Granulomas and large cells with many nuclei may be observed. The eggs elicit a granulomatous immunological response from the host that is characterised by lymphocytes (which mostly produce T-helper-2 cytokines such as interleukins 4, 5, and 13), eosinophils, and activated macrophages. This granuloma formation results in persistent inflammation.

- As a result of infection, the antibodies of the host bind to the tegument of the schistosome. Yet, they are swiftly eliminated because the tegument itself is lost every few hours.

- Moreover, schistosomes can absorb host proteins. Schistomiasis can be split into three phases: (1) the migratory phase, which lasts from penetration to maturity, (2) the acute phase, which begins when the schistosomes begin to produce eggs, and (3) the chronic phase, which primarily occurs in endemic regions.

- In the later stages of the infection, an extra-urinary complication known as Bilharzial cor pulmonale may develop. Blood in the urine (haematuria) is the distinctive sign of urogenital schistosomiasis, which is frequently accompanied by frequent urination, painful micturition, and soreness in the groyne.

- In endemic places, haematuria is so common that it is mistaken for a normal indication of puberty in boys and for menstruation in girls.

- Under severe infection, the urinary system can become obstructed, resulting in obstructive uropathy (hydroureter and hydronephrosis), which can be made worse by bacterial infection and kidney failure. Chronic bladder ulcers and bladder cancer develop in the most severe form of the illness.

Hosts of Schistosoma haematobium

Schistosoma haematobium is the parasite responsible for schistosomiasis. Schistosoma haematobium’s intermediate host is a freshwater snail of the genus Bulinus, which is widespread throughout Africa and the Middle East. The adult worms reside in the veins that drain the bladder, causing inflammation and tissue damage. Schistosoma haematobium is transmitted to humans through contact with contaminated water, typically during swimming or bathing. The condition can produce numerous symptoms, such as bloody urine, abdominal pain, and diarrhoea. Therapy typically consists of antiparasitic medications and steps to avoid further infections, such as enhancing sanitation and providing access to clean water.

Diagnosis of Schistosoma haematobium

- Historically, diagnoses have been made by examining the presence of eggs in the urine. In persistent infections or when eggs are difficult to locate, an intradermal injection of schistosome antigen to generate a wheal is a reliable method for diagnosing infection.

- Other diagnostic methods include complement fixation assays. As of 2012, commercial blood tests included the ELISA and indirect immunofluorescence assays, however their sensitivity ranges from 21% to 71%.

Prevention of Schistosoma haematobium

- Schistomiasis is mostly caused by the introduction of human faeces into water systems. The disease could be eliminated through the hygienic disposal of trash.

- In endemic places, drinking and bathing water should be boiled. Avoid water that is infected.

- Yet, agricultural activities such as fishing and rice cultivation need prolonged water contact, making avoidance impracticable.

- Snail eradication by a systematic approach is a successful way.

Facts about Schistosoma haematobium

- The parasitic flatworm Schistosoma haematobium causes the diseases schistosomiasis and bilharzia.

- It is one of the five human-infecting Schistosoma species.

- Schistosoma haematobium is present across Africa, the Middle East, and the islands of the Indian Ocean.

- Larvae of the parasite are discharged into the water by infected freshwater snails, where they can penetrate human skin upon contact with infected water.

- The parasite then grows in the veins surrounding the bladder and excretes eggs through the urine.

- The transmission of Schistosoma haematobium infection occurs by contact with contaminated water.

- The disease is especially prevalent in rural, underprivileged communities with inadequate access to potable water and sanitation.

- In many regions of Africa, Schistosoma haematobium infection is considered to be endemic.

- Schistosoma haematobium affects an estimated 112 million people around the world.

- Blood in the urine, painful urination, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, and exhaustion may be symptoms of a Schistosoma haematobium infection.

- The degree of symptoms may vary according on the duration and severity of an infection.

- Schistosoma haematobium infection is diagnosed by finding parasite eggs in a urine sample or a bladder or ureter biopsy.

- Praziquantel is the most common medicine used to treat Schistosoma haematobium infection.

- Generally, treatment is well tolerated and side effects are minor.

- If left untreated, a Schistosoma haematobium infection can cause persistent health issues such as bladder and kidney damage.

- Persistent infections can cause renal failure, and in extreme circumstances, they can be fatal.

- The transmission of Schistosoma haematobium can be avoided by avoiding contact with polluted water.

- Swimming or wading in freshwater while wearing protective equipment can also lower the risk of infection.

- Schistosoma haematobium infection can also be avoided by providing safe drinking water and proper sanitation.

- Treatment of sick persons is also essential for avoiding the infection’s spread.

FAQ

What is Schistosoma haematobium?

Schistosoma haematobium is a parasitic flatworm that causes a disease called schistosomiasis or bilharzia. It is one of the five species of Schistosoma that infect humans.

How is Schistosoma haematobium transmitted?

Schistosoma haematobium is transmitted through contact with contaminated water. The parasite’s larvae are released from infected freshwater snails into the water, where they can penetrate human skin during contact with infected water. The parasite then matures in the veins around the bladder and releases eggs, which are excreted in the urine.

What are the symptoms of Schistosoma haematobium infection?

The symptoms of Schistosoma haematobium infection can vary depending on the duration and intensity of the infection. Symptoms may include blood in the urine, painful urination, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and fatigue.

How is Schistosoma haematobium diagnosed?

Diagnosis of Schistosoma haematobium infection is made by identifying the parasite’s eggs in a urine sample or a biopsy of the bladder or ureter.

How is Schistosoma haematobium treated?

The most commonly used drug for treating Schistosoma haematobium infection is praziquantel. This medication is usually given as a single dose. Treatment is generally well-tolerated, and side effects are usually mild.

How can Schistosoma haematobium infection be prevented?

Schistosoma haematobium infection can be prevented by avoiding contact with contaminated water, wearing protective clothing when swimming or wading in freshwater, and practicing good hygiene. It is also important to treat infected individuals and to provide safe drinking water and adequate sanitation.

Where is Schistosoma haematobium found?

Schistosoma haematobium is found in parts of Africa, the Middle East, and the Indian Ocean islands.

How common is Schistosoma haematobium infection?

Schistosoma haematobium infection is considered to be endemic in many parts of Africa, with an estimated 112 million people infected worldwide. The infection is most common in rural and impoverished communities with poor access to safe drinking water and sanitation.

What is the long-term outlook for someone with Schistosoma haematobium infection?

If left untreated, Schistosoma haematobium infection can lead to chronic health problems such as bladder and kidney damage, which can result in renal failure. In severe cases, the infection can be fatal. However, with proper treatment, the prognosis is generally good.

References

- Nelwan ML. Schistosomiasis: Life Cycle, Diagnosis, and Control. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2019 Jun 22;91:5-9. doi: 10.1016/j.curtheres.2019.06.001. PMID: 31372189; PMCID: PMC6658823.

- Nelwan, M. L. (2019). Schistosomiasis: Life Cycle, Diagnosis, and Control. Current Therapeutic Research, 91, 5–9. doi:10.1016/j.curtheres.2019.06.0

- Rose, Matthew & Zimmerman, Eli & Hsu, Liangge & Golby, Alexandra & Saleh, Emam & Folkerth, Rebecca & Santagata, Sandro & Milner, Danny & Ramkissoon, Shakti. (2014). Atypical presentation of cerebral schistosomiasis four years after exposure to Schistosoma mansoni. Epilepsy & Behavior Case Reports. 2. 10.1016/j.ebcr.2014.01.006.

- https://www.cartercenter.org/resources/pdfs/health/schistosomiasis/schisto-disease-cycle.pdf

- https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/schistosomiasis/index.html

- https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Schistosoma_haematobium/